In This Content

Right to Education

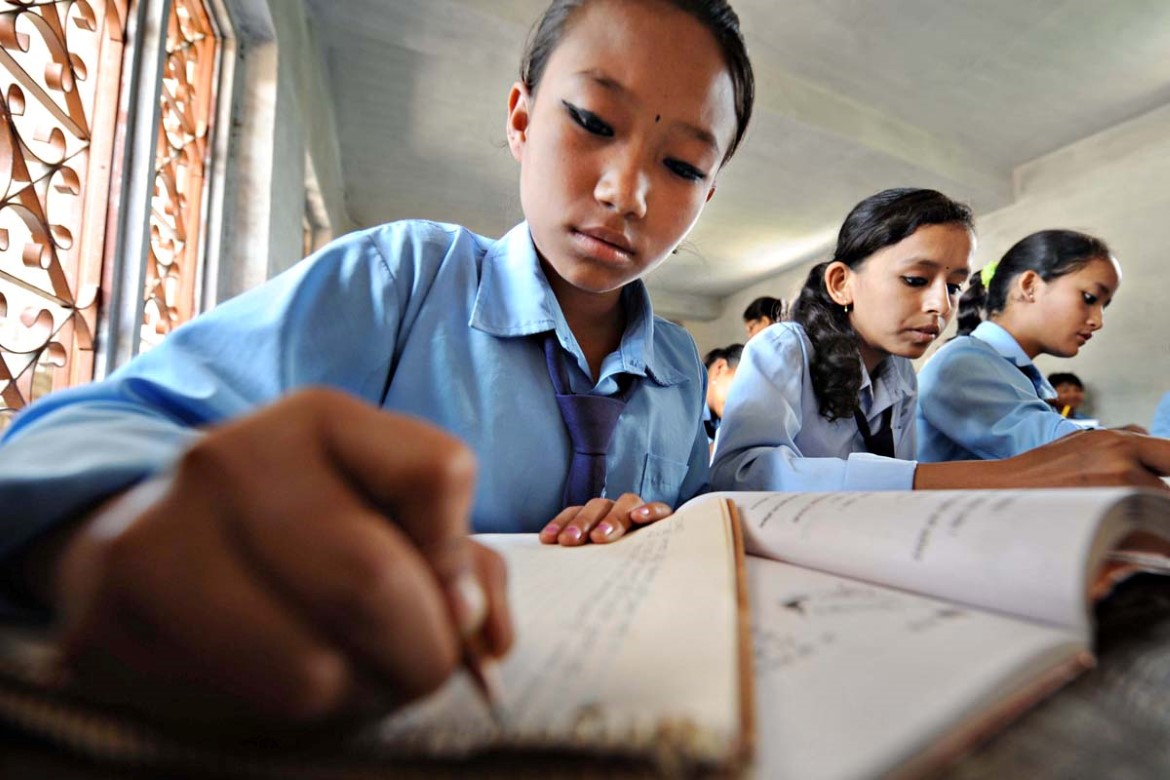

Education is a fundamental human right and essential for the exercise of all other human rights. It promotes individual freedom and empowerment and yields important development benefits. Yet millions of children and adults remain deprived of educational opportunities, many as a result of poverty.

Normative instruments of the United Nations and UNESCO lay down international legal obligations for the right to education. These instruments promote and develop the right of every person to enjoy access to education of good quality, without discrimination or exclusion. These instruments bear witness to the great importance that Member States and the international community attach to normative action for realizing the right to education. It is for governments to fulfill their obligations both legal and political in regard to providing education for all of good quality and to implement and monitor more effectively education strategies.

Education is a powerful tool by which economically and socially marginalized adults and children can lift themselves out of poverty and participate fully as citizens.

India is home to 19% of the world’s Children. What this means is that India has the world’s largest number of youngsters, which is largely beneficial, especially as compared to countries like China, which has an ageing population.

The not-so-good news is that India also has one-third of the world’s illiterate population. It’s not as though literacy levels have not increased, but rather that the rate of the increase is rapidly slowing. For example, while total literacy growth from 1991 to 2001 was 12.6%, it has declined to 9.21%.

To combat this worrisome trend, the Indian government proposed the Right to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, making education a fundamental right of every child in the age group of 6 to 14.

The right to education is a universal entitlement to education. This is recognized in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights as a human right that includes the right to free, compulsory primary education for all, an obligation to develop secondary education accessible to all, in particular by the progressive introduction of free secondary education, as well as an obligation to develop equitable access to higher education, ideally by the progressive introduction of free higher education.

The right to education also includes a responsibility to provide basic education for individuals who have not completed primary education. In addition to these access to education provisions, the right to education encompasses the obligation to rule out discrimination at all levels of the educational system, to set minimum standards and to improve the quality of education.

International Recognition of Education as a Human Right

There are a large number of human rights problems, which cannot be solved unless the right to education is addressed as the key to unlock other human rights. The right to education is clearly acknowledged in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted in 1948, which states:

“Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit……” (Article 26)

Apart from UDHR, right to education is affirmed, protected and promoted in numerous international human rights treaties, such as the following:

· Convention concerning Discrimination in Respect of Employment and Occupation (1958) – Article 3

· Convention against Discrimination in Education (1960)

· International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966) – Article 13

· Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) (1981) –Article 10

· The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) – Article 28 & 29

The right to education has therefore long been recognized by these international treaties as encompassing not only access to educational provision, but also the obligation to eliminate discrimination at all levels of the educational system, to set minimum standards and to improve quality. With respect to applicability of these treaties in India, it is worthwhile to mention that India is a State party to the ICESCR, the CERD Convention, the CEDAW Convention and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The prominent organizations around the world striving for promotion of Right to Education are:

1. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

2. United Nation Children’s Fund (UNICEF)

3. World bank

4. International Labour Organization (ILO)

Right to Education in India: Implications and Challenges

The enactment of the fundamental right to education, still in Parliamentary process but widely expected to become reality soon, is ambitious for a country that has witnessed decades of policy failure to make operational the rhetoric of free and compulsory elementary education for all children until the age of 14. Education has been neither free nor compulsory. For the state to guarantee education provision through a legislative enactment is a major shift, given a history of provision which has consistently failed disadvantaged groups, privileging the interests of a minority urban elite. About 110 million children remain out of the schooling system, and about 60% of those who enroll in school drop out by grade 8 (Wadhwa 2001). As studies have consistently shown over time, those excluded continue to reflect inequalities within the wider social, economic and political fabric, particularly those of caste, class, and gender. Axes of inclusion are broadly predicted around the following occupational and social classifications – children of the upper castes or from smaller families, or from households that are economically better off or dependent on non-agricultural occupations, with parents who are better educated, or from villages that have better access to schools (Vaidyanathan and Nair 2001) – thus underlining the roles played by social position, economic opportunity and the power exercised by local community leadership in securing state provided resources in education. Cutting right across these axes is the gender gap, which is more or less consistent across social groups.

The gap between discourse and operational framework in all policy efforts in education, and more widely development, has long been cited as a reason for India’s poor performance in securing equitable educational opportunity for all. Despite a range of commitments made in the Indian Constitution to equality, addressing the historical disadvantage faced by certain groups, and universal education, policies on the ground have done little to fulfil the ambitious vision developed at the birth of the modern Indian nation-state. This gap appears in danger of persisting, even with the shift to guaranteeing the right to education. In this section, some of the issues raised by the current approach are explored.

Right to Education in Indian Constitutional Perspective

The Indian Constitution is known to be a document committed to social justice. As per expert opinion, literacy forms the cornerstone for making the provision of equality of opportunity a reality. The Indian Constitution has therefore recognized education as the essence of social transformation, as is evident from its education specific Articles.

The judicial decision from which the right to education emanated as a fundamental right was from the one rendered by the Supreme Court in Mohini Jain v. State of Karnataka. In this case the Supreme Court through a division bench comprising of justice Kuldip Singh and R.M. Sahai, deciding on the constitutional of the practice of charging capitation ee held that:

‘ the right to education flows directly from the right to life. The right to life and the dignity of an individual cannot be assured unless it is accompanied by the right to education.’

The rationality of this judgment was further examined by a five judge bench in J.P. Unnikrishnan v. State of Andhra Pradesh where the enforceability and the extent of the right to education was clarified in the following words:

“The right to education further means that a citizen has a right to call upon the State to provide educational facilities to him within the limits of its economic capacity and development.”

The same has also been reiterated by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in Bandhua Mukti Morcha, etc v. Union of India specially referred to the earlier judgment made in this connection as under:

“In Maharashtra State Board of Secondary and Higher Education v. K.S. Gandhi, right to education at the secondary stage was held to be a fundamental right. In J.P.Unnikrishnan v. State of Andhra Pradesh, a constitution Bench had held education upto the age of 14 years to be a fundamental right…. It would be therefore incumbent upon the State to provide facilities and opportunity as enjoined under Article 39 (e) and (f) of the Constitution and to prevent exploitation of their childhood due to indigence and vagary.”

Space and Place for Claiming the Right to Education

The ‘right’ to education provides a framework for accepting that basic education is an entitlement of each and every citizen regardless of religious, ethnic or caste affiliation or identity, gender or class, disability or ability. However the focus on access, as argued earlier, limits the agenda to a very narrowly framed policy agenda which is concerned more with meeting international targets for enrolment and universalisation, than with taking into account some of the traditional relationships which have shaped exclusion. Little has been done to alter in a meaningful way the relationships between state administrators, elite village leadership, teachers and the poorer, low-caste groups within their communities (Subrahmanian 2000). Without an attempt to reorder these relationships through building alternative spaces and processes for hearing the perspectives of those excluded on what underpins their exclusion, what they feel about the education on offer, and how they see education fitting into their economic and social survival strategies, the right to education will have limited teeth for those who really would rely on it. Whilst many of these spaces are beginning to emerge in relation to education, far greater consolidation of these different actor groups is required through processes that enable excluded groups to develop and express voice. In this section, a brief assessment is made of the spaces and places within which participation in education takes place, is absent or needs to be strengthened.

At present, legal spaces for holding the state accountable to its version of student ‘rights’ provide one option. However, as discussed above, these spaces are in themselves insufficient to provide leverage, and further only recognise the rights of those already ‘included’. Education ‘guarantee’ schemes, such as those in operation in Madhya Pradesh (and now a national commitment under the new ‘umbrella’ policy for universalising elementary education, the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan), ‘guarantee’ schools in unserved areas that demand them, but again, the type of schools, their quality and content fall outside the scope of citizen action and are controlled solely by the state. With increasing levels of donor funding directed towards the state and the attempt to consolidate policy spaces under sector and sub-sector approaches, there is the risk of further crystallising the authority of the state over civil society and other organisations, and reducing transparency. While NGOs have been important innovators in education, especially in recent times, many of their ‘models’ are being absorbed directly into state programmes, without clear analysis of what it is these models offer and what insights they provide into developing localised education strategies based on community ownership. Even where ‘community participation’ is invoked, as it is increasingly in state programmes, there are insufficient attempts to address the foundational bases of inequality that prevent the most disadvantaged groups from expressing their views (see Subrahmanian, forthcoming). Village Education Committees (VECs), heralded as the new face of community participation in education, are often bureaucratised forms of citizen voice formed with a view to rounding children up and sending them to school rather than eliciting the views of parents on what education content and delivery should be.

Right to Education Act

The Right of children to Free and Compulsory Education Act came into force from April 1, 2010. This was a historic day for the people of India as from this day the right to education will be accorded the same legal status as the right to life as provided by Article 21A of the Indian Constitution. Every child in the age group of 6-14 years will be provided 8 years of elementary education in an age appropriate classroom in the vicinity of his/her neighbourhood.

The Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Act, 2002 inserted Article 21-A in the Constitution of India to provide free and compulsory education of all children in the age group of six to fourteen years as a Fundamental Right in such a manner as the State may, by law, determine. The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009, which represents the consequential legislation envisaged under Article 21-A, means that every child has a right to full time elementary education of satisfactory and equitable quality in a formal school which satisfies certain essential norms and standards.

Article 21-A and the RTE Act came into effect on 1 April 2010. The title of the RTE Act incorporates the words ‘free and compulsory’. ‘Free education’ means that no child, other than a child who has been admitted by his or her parents to a school which is not supported by the appropriate Government, shall be liable to pay any kind of fee or charges or expenses which may prevent him or her from pursuing and completing elementary education. ‘Compulsory education’ casts an obligation on the appropriate Government and local authorities to provide and ensure admission, attendance and completion of elementary education by all children in the 6-14 age group. With this, India has moved forward to a rights based framework that casts a legal obligation on the Central and State Governments to implement this fundamental child right as enshrined in the Article 21A of the Constitution, in accordance with the provisions of the RTE Act.

The RTE Act provides for the:

· Right of children to free and compulsory education till completion of elementary education in a neighbourhood school.

· It clarifies that ‘compulsory education’ means obligation of the appropriate government to provide free elementary education and ensure compulsory admission, attendance and completion of elementary education to every child in the six to fourteen age group. ‘Free’ means that no child shall be liable to pay any kind of fee or charges or expenses which may prevent him or her from pursuing and completing elementary education.

· It makes provisions for a non-admitted child to be admitted to an age appropriate class.

· It specifies the duties and responsibilities of appropriate Governments, local authority and parents in providing free and compulsory education, and sharing of financial and other responsibilities between the Central and State Governments.

· It lays down the norms and standards relating inter alia to Pupil Teacher Ratios (PTRs), buildings and infrastructure, school-working days, teacher-working hours.

· It provides for rational deployment of teachers by ensuring that the specified pupil teacher ratio is maintained for each school, rather than just as an average for the State or District or Block, thus ensuring that there is no urban-rural imbalance in teacher postings. It also provides for prohibition of deployment of teachers for non-educational work, other than decennial census, elections to local authority, state legislatures and parliament, and disaster relief.

· It provides for appointment of appropriately trained teachers, i.e. teachers with the requisite entry and academic qualifications.

· It prohibits (a) physical punishment and mental harassment; (b) screening procedures for admission of children; (c) capitation fee; (d) private tuition by teachers and (e) running of schools without recognition,

· It provides for development of curriculum in consonance with the values enshrined in the Constitution, and which would ensure the all-round development of the child, building on the child’s knowledge, potentiality and talent and making the child free of fear, trauma and anxiety through a system of child friendly and child centred learning.

Major provisions of Right to education Act

Every child between the age of six to fourteen years, shall have the right to free and compulsory education in a neighbourhood school, till completion of elementary education.

For this purpose, no child shall be liable to pay any kind of fee or charges or expenses which may prevent him or her from pursuing and completing elementary education.

Where a child above six years of age has not been admitted to any school or though admitted, could not complete his or her elementary education, then, he or she shall be admitted in a class appropriate to his or her age.

For carrying out the provisions of this Act, the appropriate government and local authority shall establish a school, if it is not established, within the given area, within a period of three years, from the commencement of this Act.

The Central and the State Governments shall have concurrent responsibility for providing funds for carrying out the provisions of this Act.

This Act is an essential step towards improving each child’s accessibility to secondary and higher education. The Act also contains specific provisions for disadvantaged groups, such as child labourers, migrant children, children with special needs, or those who have a disadvantage owing to social, cultural, economical, geographical, linguistic, gender or any such factor. With the implementation of this Act, it is also expected that issues of school drop out, out-of-school children, quality of education and availability of trained teachers would be addressed in the short to medium term plans.

The enforcement of the Right to Education Act (External website that opens in a new window) brings the country closer to achieving the objectives and mission of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and Education for All (EFA) and hence is a historic step taken by the Government of India.

[“source=legalservicesindia”]